Mozambique. I’ve never been to it, but always known it as a place for great fish, and beautiful beach holidays, but I knew nothing about the country or it’s people prior to our visit.

Mozambique reminds me of the Africa I grew up in. A place where you could walk freely, feel no fear, need no heightened awareness. I realise that my experience of Mozambique is painfully limited to both one specific area – Ponta do Oura – and a visit, and visiting a place is very different indeed from living in it.

But, in visiting a place, you still pick up a feel for it, and you can as easily lose a piece of your heart to it as if you lived there – easier – in fact, as you don’t have to face up to the realities that can sometimes end the illusion.

The first and foremost difference I experienced in Mozambique is the safety and crime levels. In South Africa, I am unlikely to walk on my own anywhere, and certainly not after dark. In Mozambique I could walk from the restaurant (with Wifi) to the chalet freely, with my laptop, with no interference or qualms. In South Africa, you can have your window smashed at a traffic light for the handbag on your seat, but in Ponta Do Oura, we stopped in the middle of the market with all our belongings on the back of an open vehicle, and no one even looked at it all twice. The difference between the people and community spirit in two places less than 10 miles apart, separated by a border, knocked me.

The first and foremost difference I experienced in Mozambique is the safety and crime levels. In South Africa, I am unlikely to walk on my own anywhere, and certainly not after dark. In Mozambique I could walk from the restaurant (with Wifi) to the chalet freely, with my laptop, with no interference or qualms. In South Africa, you can have your window smashed at a traffic light for the handbag on your seat, but in Ponta Do Oura, we stopped in the middle of the market with all our belongings on the back of an open vehicle, and no one even looked at it all twice. The difference between the people and community spirit in two places less than 10 miles apart, separated by a border, knocked me.

Another difference is in infrastructure – there’s a lot of money being pumped into that community at the moment, with holiday houses and vacation rentals being built all over, so much so that in 10 years, I doubt I’ll recognise the place – but there are no tarred roads.

In fact, the roads that were tarred when the Portuguese ran the country back in the ’70, before they were expelled and civil war ripped the country apart, destroying its wealth and throwing it into extreme poverty, developed potholes, which are now massive dongas in the road, filled with beach sand. You can’t drive around the South of Mozambique with a ‘normal’ city car. It’s physically impossible.

Houses differ, depending on the ‘wealth’ of the person owning it. When you grow up and want to move into your own place, and take a wife, you go to the chief of your tribe, and you ask him for land. He gives you land, and on that you build your house. Either out of reeds or if you can afford it, tin or stone.

As far as I could tell, these houses have no running water. Some of them have electricity, and some even have satellite TV, but that is rare. The ground is beach sand, so gardening is difficult, but here and there, people have planted lettuce, and maybe one or two other vegetables, which they sell on the side of the road to tourists.

This is poverty

I sat in the Upstairs Restaurant watching the London riots (2011) unfold on the screen and felt an emotion I don’t have the words to describe. London’s youth, rioting about what they don’t have, destroying, pillaging, murdering while in Mozambique, life goes on without running water. Without, without, and without.

And yet the people are friendly. They are warm, and open, and welcoming. Perhaps because they too have a tumultuous history, and every 30-something year old and over remembers a time where, if it’s possible, life was even harder. From a slave trading mecca to Portuguese rule, to civil war (for around 30 years) these people have been through the mill for generations. Perhaps now they just want peace. I know I felt such peace there.

We went to the local maternity unit. A three-bed ward, with a tiny, archaic birthing suite. I didn’t ask about their mortality rates, but here they only have basic facilities. If a woman has trouble, or a difficult pregnancy or birth, she has to cross the border to a hospital in South Africa – if she makes it that far.

Yet here they have faith in the woman’s ability to give birth to her baby. There isn’t really the option for assisted deliveries or emergency caesareans. Nature decides.

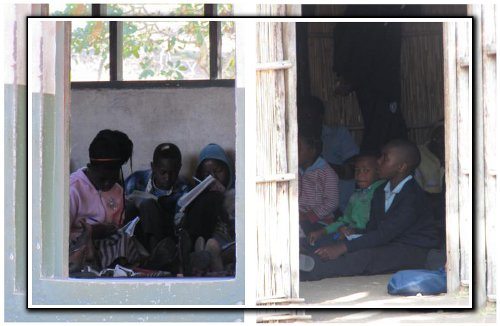

I went to the local school, and this moved me. I think it changed me, in some way.

I asked the teacher, a guy by the name of Leno, whether the children knew they were poor. He said they see the foreigners coming in big cars and paying heavily inflated prices for things while going on diving trips and they know they are poor.

He said “We know we are poor. Our children sit on the floor to learn. We don’t even have desks for them. But we teach them that this is where they start, but from here they can make their lives better.”

What optimism. What hope!

This is a small school. They have 2 sittings, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. There are more children than room, so they have to do it this way. 80 – 100 children per session. The lucky ones have class in the morning, so they can walk to school in the dark and as the sun rises – some of them walking up to 7km on soft beach sand roads to get to school, then making that journey home again in the scorching heat of the day. The afternoon children have to do the journey in the heat both ways.

This is a small school. They have 2 sittings, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. There are more children than room, so they have to do it this way. 80 – 100 children per session. The lucky ones have class in the morning, so they can walk to school in the dark and as the sun rises – some of them walking up to 7km on soft beach sand roads to get to school, then making that journey home again in the scorching heat of the day. The afternoon children have to do the journey in the heat both ways.

And these are children. From six years old.

Again, these are the lucky ones. In the next region, some children have to walk up to 15km one way to get to school each day.

School finishes for them when they’re around fifteen, and those who have parents who can afford to send them to secondary school go off to Maputo, 100 miles away, living with family or friends to finish school. But often – and I heard this from a woman in town – the girls leave school then, because “they’ve been impregnated by the teachers by that stage”.

(One of the teachers told me he is happy when the maternity unit is full – it means he’ll always have a job. I shudder now to think what he might have actually meant. )

I sat for a while, under a tree in the centre of the school, listening to the sounds of engaged children, learning, lapping it up. I wondered what they would say if they saw the schools in England, what our children have, what they have available to them. I wondered how they would feel if they knew how we’ve taken so much for granted.

I sat for a while, under a tree in the centre of the school, listening to the sounds of engaged children, learning, lapping it up. I wondered what they would say if they saw the schools in England, what our children have, what they have available to them. I wondered how they would feel if they knew how we’ve taken so much for granted.

I watched a little girl run up the hill to the outdoor bush toilets, and run back down and back to class. I remembered how long I used to linger in the hallways or bathrooms to miss as much of ‘class time’ as I could. I wondered if she could fathom that.

Maybe it was watching London burn on TV, and following the twitter stream of conversations surrounding it, on top of being in this – I’d say god-forsaken place, except I think the people are quite religious – place that civilisation forgot. Perhaps it was just the place itself, or the people, or the freedom of movement, the lack of crowds, and the extreme absence of commercialism and materialism, but in something in this little corner of the world, flanked by nothing and ocean, I found a small voice in my heart crying out for the peace, and the simplicity of this life.

It’s an amazing capabilities to draw lines between such distant realities and make other people think. Thank you for this post

I am loving hearing about your travels! It’s my dream to see some of these places one day.

It’s always very interesting to go and see somewhere less developed than where you are living and here you talk about Mozambique. Must be very moving, seeing the differences,what we take for granted and what they need…Thanks for sharing.